The Case of Nonprofits – Nonprofits and Working for Social Change

Nonprofits and working for social change

Nonprofits in the policy process

Understanding the broad range of nonprofit work, this section focuses on these organizations’ roles and the influence they might have on the policy process. For Albert Wat, senior policy director at Alliance for Early Success, the sector can be defined from an advocacy perspective by looking at the different areas or levels where NPOs tend to work.

A key aspect mentioned is collaboration. Nonprofit organizations often consider entering or forming coalitions to push for significant policy reforms. Buffardi et al. (2017) found that organizations that collaborate are viewed as more effective for enacting proactive policy changes than those that are not11Ward, K. D., Mason, D. P., Park, G., & Fyall, R. (2022). Exploring Nonprofit Advocacy Research Methods and Design: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 1-22..

Interorganizational pathways to social change

The complex landscape posed by the amount and variety of nonprofits specializing in advocacy efforts and participating in the policy process might be the main reason collaboration efforts have become key to approaching policy issues. Nonprofits can organize among themselves, which usually takes the form of coalitions. Organizations agree to work toward a common goal or goals, while each maintains their autonomy. This means they might have diverse purposes or missions, but they decide to work toward a common goal. NPOs can also form partnerships. In this form of collaboration, as few as two organizations can join their capacities, resources, and expertise, aligning their objectives and strengths to achieve a mutually beneficial goal12Mizrahi, T., Rosenthal, B. B., & Ivery, J. (2012). Coalitions, Collaborations, and Partnerships: Interorganizational Approaches to Social Change. In Weil, M., Reisch, M. S., Ohmer, M. L., & Ohmer, D. M. L. (Eds.), The Handbook of Community Practice (2nd ed., p. 383-402). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976640.n17 .

However, another type of collaboration has become increasingly relevant—nonprofit organizations and the government. As mentioned before, there was a point in history when the federal government started relying on NPOs to privately deliver publicly financed goods and services. Since then, this public-private relationship has expanded with government support outdistancing private philanthropic support. These relationships can take many forms and may include contracts, grants, third-party payments, tax deductions and exemptions, privatization, joint ventures (public-private partnerships), advocacy, and policy change13Mason, D. P. (2022). Introduction to the Nonprofit Sector. University of Oregon. https://opentext.uoregon.edu/intrononprofit/ .

The interdependence theory explains how these patterns of collaboration formed as a natural consequence and emphasizes the interdependence between the state and various other social actors. In other words, the government depends on the NPO sector to deliver certain services, while the NPO sector depends on the government for funding. In this way, it sees the strengths of the nonprofit sector as a provider of goods or services as a complement to the limitations of government in originating and delivering those same goods, while considering the strengths of government as a generator of revenue and rights to benefits as a complement to the limitations of the NPO sector in those areas14Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (2015). Government-Nonprofit Cooperation: Anomaly or Necessity?. Voluntas: International Society for Third-Sector Research, 26, 2155–2177. .

Rose states nonprofit organizations can become vital partners, not just because of the services or goods they can deliver, but also as key connections between the communities and the government and as advocators who can hold them accountable. These public’s needs and challenges are so big and complex that they rarely can be addressed alone. Multiple actors and resources must solve them. In this way, partnerships can develop strategic direction and coordination to achieve a scale and integration of services that would be otherwise impossible alone15Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government-Nonprofit Partnership: A Defining Framework. Public Administration and Development, 22(1), 19–30..

Government-Nonprofit partnerships

The development of a government-nonprofit partnership involves substantial transaction benefits and costs to both parties, with complex interdependencies at play16Smith, S.R. & Grønbjerg, K.A. (2006). Scope and Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations. In Powell, W.W. & Steinberg, R. (Eds.) The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. (pp. 221–242). Yale University Press.. In a very simple way, it can be defined as a dynamic relationship that entails reciprocal obligations and mutual accountability, a sharing of investment (not only financial), reputational risks, and collective responsibility in the design and execution of common goals. These collaborative mechanisms have allowed for the expression of power in the community, an exercise of engaged civil society, and the creation of business opportunities17Mendel, S. C. & Brudney, J. L. (2012) Putting the NP in PPP: The role of nonprofit organizations in public-private partnerships. Public Performance & Management Review, 35(4), 617–642..

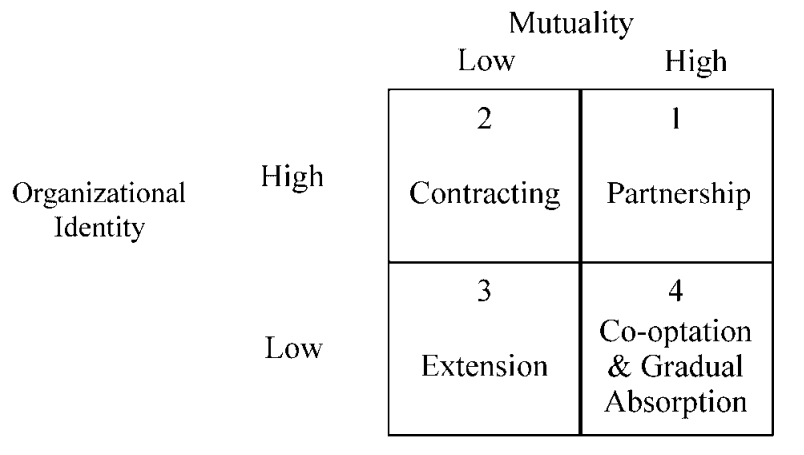

To analyze if an interorganizational relationship is operating as a partnership, look at two of its defining dimensions: mutuality and organizational identity. The first points to the respective rights and responsibilities of each actor to the other, a mutual commitment to the partnership’s goals, and the assumption that these are consistent and support each organization’s own mission and objectives, leading to equality in decision-making. The latter refers to those characteristics that are distinctive and enduring in an organization. Each actor maintaining its core values and beliefs across time and contexts is essential to the partnership’s long-term success18Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government-Nonprofit Partnership: A Defining Framework. Public Administration and Development, 22(1), 19-30..

Partnership Model

Brinkerhoff (2002) provides a graphic model that can help understand and examine interorganizational relationships (Figure 2). When there is a high level of mutuality, accompanied by high organizational identity among the actors, a collaborative effort can be said to be a partnership. However, because all relationships are dynamic, subtle leanings toward other types of alliances can occur, especially over time.

*If you’re interested in diving deeper into the theory behind the model, Brinkerhoff (2002) provides further definitions and examples of each type of alliance.

Citations

- 11. Ward, K. D., Mason, D. P., Park, G., & Fyall, R. (2022). Exploring Nonprofit Advocacy Research Methods and Design: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 1–22.

- 12. Mizrahi, T., Rosenthal, B. B., & Ivery, J. (2012). Coalitions, Collaborations, and Partnerships: Interorganizational Approaches to Social Change. In Weil, M., Reisch, M. S., Ohmer, M. L., & Ohmer, D. M. L. (Eds.), The Handbook of Community Practice (2nd ed., p. 383–402). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412976640.n17

- 13. Mason, D. P. (2022). Introduction to the Nonprofit Sector. University of Oregon. https://opentext.uoregon.edu/intrononprofit/

- 14. Salamon, L. M., & Toepler, S. (2015). Government-Nonprofit Cooperation: Anomaly or Necessity?. Voluntas: International Society for Third-Sector Research, 26, 2155–2177.

- 15. Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government-Nonprofit Partnership: A Defining Framework. Public Administration and Development, 22(1), 19–30.

- 16. Smith, S.R. & Grønbjerg, K.A. (2006). Scope and Theory of Government-Nonprofit Relations. In Powell, W.W. & Steinberg, R. (Eds.) The Nonprofit Sector: A Research Handbook. (pp. 221–242). Yale University Press.

- 17. Mendel, S. C. & Brudney, J. L. (2012) Putting the NP in PPP: The role of nonprofit organizations in public-private partnerships. Public Performance & Management Review, 35(4), 617–642.

- 18. Brinkerhoff, J. M. (2002). Government-Nonprofit Partnership: A Defining Framework. Public Administration and Development, 22(1), 19–30.